https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/why-blackberry-suddenly-so-hot-again-chris-rafter?trk=prof-post

Seven Ways To Help Employees Execute Your Strategic Plan

How to help employees and coworkers unmask and be themselves at work

The Art of Failing Forward

The threat of Failure haunts us throughout our education. When you fail in school, it meant you were not good enough, and that you would be held back. When you fail a test, it is your mistakes holding you back, and the penalty was you had to do it all over again, even the parts you got right. This teaches people to fear failure, rather than see it for what it is.

Thankfully, school is not like real life. Success is the result of hard work coupled with an ability to learn from mistakes, and correct on-the-fly. In other words, you’ll never succeed unless you learn to fail productively. It’s what Silicon Valley entrepreneurs and innovators call Failing Forward. It’s the art of using a regular and expected cycle of failures to ultimately produce success.

But how can a whole bunch of failures strung together result in success? That seems counter-intuitive. In fact, failure and success are not two sides of the same coin. Success is not the opposite of failure, success is a final destination, and failure is merely a step in the wrong direction. Think about how a guided missile works. The missile’s job is to hit a tiny target 500 miles away. When the missile is in flight, it is constantly being pushed off course by wind and gravity. It’s guidance system takes hundreds of readings every second on course and position, and makes minute corrections to get it back on course. These tiny course errors are nothing to the guidance computer. They would only be a problem if the guidance system ignored them, allowing the missile to go 20, 30 miles off course or hit something else.

It doesn’t matters much at all where the missile is pointed at any point during the flight. All that matters is that it knows A) where it is B) where the target is in and C) that it can to quickly correct course as necessary until finally, it hits its target.

Successful failing is a lot like this. When asked about his many failed designs when inventing the electric light bulb Thomas Edison said, “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”. Lots of people have figured this out already. In Silicon Valley, failure is celebrated. The only true failure, is failing to learn from a mistake.

In people, it’s the willingness to try something new, take a risk, knowing that you’ll either succeed, or you’ll learn something. Either way, that’s a positive. So if every time you follow this cycle, something good happens to you, then repeating the cycle as often results in more good things happening. Smart learning and fast recovery are as important as fast experimentation. The top innovators and winners in Silicon Valley have figured this out: The willingness to fail, and the ability to learn and recover quickly is far more likely to lead to success than even the best idea.

There is a saying in product development that sounds harsh, but makes perfect sense: Kill off the bad ideas as quickly and as early as possible. To do that requires an almost superhuman level of discipline. You have to be willing to pivot quickly, to say goodbye to something you may have put years of work and thought into.

Most of us are taught the opposite. We are taught to think a lot, and to try to make things perfect before we launch. It’s a very romantic notion, the craftsman or designer putting hours of thought and effort into something, polishing it and making it so perfect that customers will just swoon when it’s finally released. It seems a lot less noble to be the guy who floods the market with half-baked product ideas and always seems to be coming up with something new.

So what exactly is wrong with the “traditional” approach?

Trying to get everything right in a few iterations is impossibly hard. You simply don’t know what you don’t know. If you only have a few iterations, you get careful, because you wouldn’t want to take any risks that might increase your chances of failure. Now you’ve stopped taking risks, you’ve stopped innovating, and soon you’re in a death spiral. This is what so often happens with big companies who have had a few successes, and why smaller companies run laps around them in the innovation department.

Back in 2006, the Blackberry was the #1 smartphone. Then Apple decided to design a phone, and it could take risks because it had little to lose. If the phone was a flop, they would try again with something else. Not Blackberry, however. Their response to the revolutionary iPhone was minor enhancement to the Blackberry device. They did this because they didn’t want to risk losing their loyal customers if they deviated too much from the traditional Blackberry formula. So what happened to Blackberry’s customers? They lost them anyway.

Having a product out there and learning from it is vastly more efficient than thinking and deliberating over what the best product might be. Silicon Valley companies go out of their way to enter uncharted territory. The fact is nobody is capable of predicting every little detail or nuance of how your idea might go. It’s like trying to pre-program every little course correction going into that guided missile’s path. Once you accept that it’s impossible, don’t spend another second worrying about it. As much as we deliberate, we will always be wrong about something. So the faster we start gathering and responding to feedback, the more we learn. I’d much rather be hearing from actual customers about how they feel about my product than sitting locked in a basement, trying to guess at what features they will want.

This explains why many big companies are outmaneuvered by start-ups. The executives in big companies are equally smart, and often work equally hard. They know their current customers really well. Big companies also fear losing existing customers, so they reject any ideas that might risk this. It’s easy to inspire caution in large companies. When you have a lot to lose, fear quickly overshadows the entrepreneurial spirit. So in big companies, people talk about perfection, they convince themselves of something that is never true: That if they just work hard enough, they’ll get it perfectly right, and we all know how that story ends.

Chris Rafter is a technology executive, writer, speaker and thinker. Reach him at chrisrafter@gmail.com

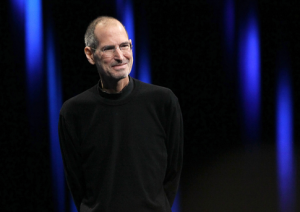

How Steve Jobs would have handled the iPhone 6 and Apple Watch launch

While I think Apple has still retained nearly all of the creativity and innovation it has always had, this article precisely details where they slipped up with last week’s product launch of the iPhone 6 and Apple Watch:

- Caving to launch a larger phone just because competitors have one, without having a great reason to do so, not having an opinion on the ideal design

- Missing the chance to story-tell about the Watch and Apple Pay as an experience, rather than a couple of products

- Diluting the recognizability of the Watch by having dozens of different colors and flavors

It also nails how Steve would have done it!

If You’re Not Delivering $300-Per-Hour In Value To Your Prospect, They’re Wishing You Would Stop Talking

Article by Chris Rafter, MBA

There’s an ugly truth about sales prospecting: most of the time, the bored client wishes they were somewhere else. Often the content is mismatched to their needs, or the sales representative is just droning on about a boring topic and putting the client to sleep. People are good actors, they’ll seem to be listening, and even appear interested, then they’ll thank you politely and hope that they never hear from you again. Have you ever wondered what actually happened? Why the client just “went dark”?

Prospects do like to be engaged, drawn in, and most of all rewarded for the time they invest with you. Like any investor, prospects like to have a return on their investment.

It’s a very simple rule I have taught my sales teams for years: Always approach a client meeting by asking yourself “Am I bringing at least $300-per-hour of value to this client?”. If you’re not, or you can’t think of a way you could, you’re not prepared for that meeting and you’re actually asking the client for a handout. What’s the handout? Their time, of course. Why $300? It’s what most executives value an hour of their time at. When you set out to deliver value, rather than sell to someone, the equation shifts dramatically. Suddenly the prospect wants to be there, they’re leaning forward, writing down what you’re saying. They’re engaged. Now there’s something in it for them. In fact, it starts to feel less like selling and more like two people helping each other. Which type of meeting would you rather be in?

You might argue “But my manager says I’m there to sell something.” Prospects don’t see it that way, they don’t want to be sold to. They want to be listened to and helped. If you’re not doing one of those two things, you’re wasting their time and yours. They are looking for a resource that can help them in as many parts of their business as possible. They know they can easily pick up the phone and call any company to order something. The odds of them calling you are no better than of them calling one of your competitors. However, if you are the one sales person who is helping them succeed on a professional, business and personal level, you just made their short list of very important people, and closed business will find you. Once that starts happening, your Sales Manager is not going to care which approach you used.

The best way to start doing this is to just do it, start asking the question of yourself, and do your best to answer it. Once you start, it becomes a habit. Think about the next meeting you have scheduled. Will the client get $300-per-hour of value out of it? Are they going to leave the meeting feeling it was the highlight of their day? If the answer is no, then do something about it. The best part about this method is that it’s 100% free. You don’t have to bring a gift and I’m definitely not suggesting you bribe anyone. Look around you, inside your network of contacts, in what you know about that prospect to find out what they might want that you’re capable of giving them.

Most of us are capable of delivering a lot more value than we think. The more time we take and the better we know someone, the easier it becomes. A great place to begin delivering value is to do your homework. Talk to your prospect, talk to their colleagues or current vendors.

What kind of solution would make this person’s life easier?

What does a home-run look like to them?

If they could change anything about their job, what would it be?

These three questions all focus on the client, not on your product. By shifting the perspective and actually listening, you’ll earn their attention and trust. Send a brief pre-meeting email asking what they’d like to get out of the meeting. Go ahead and be a bit daring, ask what an overwhelming success would look like. Invite them to challenge you. If they say “I’d just like to learn about your products,” ask what that would look and feel like. (Is there anything more aggravating than a salesperson who holds information hostage until you meet with them?)

If the prospect is evaluating you, chances are they’re researching your competition too. Can you do some freelance research on your competitor’s product beforehand and present a comparison? The prospect is probably going to have to do that comparison anyway, and you just successfully dodged the prospect meeting with your competition and saved them a few hours work. Guess what, now you’re doing it! All it takes is a little empathy and healthy dose of creativity. The most important part is keeping the rule in mind for every meeting.

There are hundreds of ways you can practice this policy, limited only by your imagination. The best way to get started is simply to start asking, getting meetings will become effortless. Your clients will actually be happy to see you every time, and most of all you’ll earn the time to uncover what really goes into their buying decision, rather than guessing.

The Things Highly Confident People Don’t Do

Confidence is rarely taught, but it should be. It is often learned through experiences, but those experiences usually only come about once one adopts a certain attitude.